In Search of a Different World

On the floor of the grand hall of Dallas Love Field airport is a wonderful floor mural made out of thousands of tiles that depicts the world as it existed shortly after WWII… when the terminal was first built in 1959. So, during a recent trip through Love Field, I did what I always do: I made my way to the mural to admire it once more. However, this time, I couldn’t see it—not as well as I once could, at least. Alas, my beautiful vision of the world had been obscured underneath a maze of TSA screening stations and lines of travelers snaking through the security hall—most of them seemingly unaware of what was right under their very feet.

A Love Connection

There is a special place in my heart for Love Field—and not only because of its name (though, Love Field is still the greatest airport name in the world). I love Love Field because it was my point of departure from which I set off to see the rest of this wide world.

Young travelers accustomed to DFW International Airport might be surprised to know this, but when I was younger, most flights to and from Texas connected through Dallas Love Field. And even though I didn’t get many chances to travel when I was young, I did have the privilege of experiencing the "Love connection" on a handful of occasions (which, back in those days, meant hanging out in the airport for hours at a time, waiting for your connecting flight). As a kid with nothing better to do, what was not to like about that? Love Field fueled the love for airports that I still carry with me to this day.

A Crisp Twenty

It was also at Love Field where I had my first encounter with what I considered to be a massive amount of money. On my way from Houston to Albuquerque, where both of my sisters were living, I managed to lose the small amount of travel money my mother had given me. I barely had enough change in my pocket to call my mom on a payphone to give her the bad news. She called my godfather, Doc Stewart, who lived just off of Mockingbird Lane a few blocks away. Doc was kind enough to bring over some emergency cash—a brand new, crisp $20 bill. Twenty dollars! I’ll say it again… TWENTY WHOLE DOLLARS!

Never had I held such wealth in my own hands. It thrilled and terrified me. My mind was filled with worries: “What if I lose it again?” “What should I spend it on?” “How much will it buy?”

So, overwhelmed, I didn’t spend a dime of it; when I arrived in Houston a week later, that same bill was still safely tucked away in the Batman-themed wallet that my mother had gifted me. What an adventure in travel and money! And while that crisp $20 bill is long gone, the memory of it will remain with me to this day.

That Magical Mural

But, perhaps my greatest memory of Love Field was the moment I saw that aforementioned mural for the very first time. As someone who has always loved maps, the Love Field world mural is my most beloved—after all, they say you always remember your first.

But more than it being my foray into amateur cartography, it illustrates a rapidly-fading colonial world. It’s covered with old countries such as French Indochina, and other nations that no longer exist—namely the USSR. Some countries on the mural are not yet split up, like India (which, before it gained independence from Great Britain, included Pakistan and Bangladesh). Large swaths of Southern Africa were still a part of the “Republic of South Africa.” Countries like the romantic-sounding Madagascar had its own tile color—making it look almost as big as Europe.

The Love Field mural was incredibly interesting to me in my youth. In some ways, it’s even more interesting to me now, because it recalls a world of the past—one that no longer exists.

Nations Rise and Fall

The nations of the world have undergone dramatic geographical changes. In my lifetime, empires have fallen, colonies have become sovereign nations, and national boundaries have been arbitrarily drawn to create entirely new nations. The Cold War has come and gone; definitions of east and west have morphed across the globe, and the map of the world has morphed along with it.

Thus, the map I saw at Love Field in my youth (and indeed, the one I see today on my computer screen), is a moment frozen in time, like a snapshot of dancers doing a dip at the end of a dance number.

The airport itself and all of the people who travel through it also represent a world that has changed. 9/11 in particular changed air travel forever. So now, I can hardly see my world mural on the terminal floor. Instead, now, it’s airport security, crowds, shoes off, and computers out of their bags.

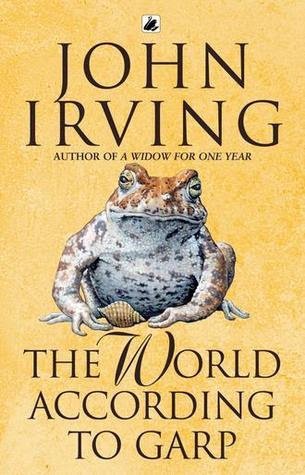

The World According to Garp

One of my favorite books (and movies) was written right around the time I first saw the Love Field world mural in the 1960s: “The World According to Garp.”

In this story, there is an eerie, recurring conversation about something called an "undertoad.”

The titular character's son—also named Garp—misunderstands his mother's warning about “the undertow” when swimming in the ocean next to their beach house. He instead hears “undertoad,” which prompts him to imagine a giant sinister toad lurking beneath the ocean depths (as opposed to, of course, the forceful currents of the sea).

Here’s an excerpt:

When Walt was old enough to venture near the water, Duncan said to him – as Helen and Garp had, for years, said to Duncan – ‘Watch out for the undertow.’ Walt retreated, respectfully. And for three summers Walt was warned about the undertow. Duncan recalled all the phrases.

‘The undertow is bad today.’

‘The undertow is strong today.’

‘The undertow is wicked today.’ Wicked was a big word in New Hampshire – not just for the undertow.

And for years Walt reached out for it. From the first, when he asked what it could do to you, he had only been told that it could pull you out to sea. It could suck you under and drown you and drag you away.

It was Walt’s fourth summer at Dog’s Head Harbor, Duncan remembered, when Garp and Helen and Duncan observed Walt watching the sea. He stood ankle-deep in the foam from the surf and peered into the waves, without taking a step, for the longest time. The family went down to the water’s edge to have a word with him.

‘What are you doing, Walt?’ Helen asked.

‘What are you looking for, dummy?’ Duncan asked him.

‘I’m trying to see the Under Toad,’ Walt said.

"Undertoad,” and the World According to Garp in general, reflected a sort of free-floating anxiety ever-present in the 1960s; anxiety about family, friendships, and losing your loved ones to elements as uncontrollable, unknowable, and unpredictable as the sea itself. It’s a world not unlike the one we live in today.

Perhaps no place has more skulking undertoads than airports in the 21st century. It’s hard to imagine, but airports of the recent past (all the way up to the 21st century), were relatively relaxed places compared to the pressure-cooker atmosphere that exists in them today. You could walk right up to the gate without going through security and sometimes even get right on the plane without a ticket—all just to say hello or goodbye to a family member before they departed.

Flying wasn’t a casual activity either. Folks dressed up to fly, and flight attendants were glamorized while treating passengers as if they were honored guests in a noble household. People would drive to the airport, park, and go up to viewing galleries in the terminal just to watch the planes come and go.

Love Field, in particular, had a great viewing gallery where you might glimpse a bright orange Braniff Airlines 747 if you were lucky. You could even bring your own food and liquor on any flight (and almost everybody did). I remember sharing a bottle of tequila with several people on a flight from California one late night back in the 1980s. Give that a try today if you want to be placed on the "no-fly" list.

How We Got Caught Up in the Undertoad

Then came terror attacks, hijackings, and entire passenger flights being shot out of the sky, or bombed, with hundreds of innocent lives lost. Even recently, some passengers have created a new kind of lite terrorism by assaulting members of the flight crew and causing entire aircrafts to divert from their destinations. On top of that, governments all over the world have hardened their airports, and the air travel experience has hardened along with it. And while all this was undoubtedly necessary, it also unleashed the undertoads. Soon, airports were no longer the happy places where non-flying folk would take their kids on Sundays to grab a hot dog and watch the planes. They became scary, stressful, and crowded—infested with undertoads of all shapes and sizes.

Air travel seems so utilitarian and one-dimensional these days. Airports are about security, processes, rules, and danger. They tend to be places that lack imagination—about how we, unfortunately, coexist along with our fears and the now very serious business of travel. Even the wonder of the world which drew me to, and through, Dallas Love Field—the wonder that was portrayed in that fabulous mural of the world right at its entrance—sometimes feels obscured, buried underneath, swept away by the undertoad.

Most folks think that airplanes travel from one point to the next in a straight line, representing the fastest route between the two points. This is mostly untrue. Flight paths tend to meander, guided by the direction of the jet stream, weather, and air traffic controls. (And in the case of one flight I took to Las Vegas, the pilot diverted out of the sheer desire to show us the Grand Canyon before we landed. That particular convolution was lovely!)

The history of travel and airports has been an ever-changing story. In the past few decades, we have swerved way off the course of delight and wonder out of necessity. The security danger was real, and steps needed to be taken. But sometimes it seems as though we’re just fighting old wars. We still take off our shoes to go through the X-ray machines because some fool tried to blow up a plane with a "shoe bomb" 30 years ago. However, like the path of an airplane, the future does not have to be a straight line from the past. And in truth, it never is. That kind of world no more exists than the world on the old Love Field mural. If we imagined a mural of our new world, what would that look like? Would it bring a sense of wonder to the little kids traveling through the airport today? In hindsight, will they remember their first flights as something of an undertoad or a freshly-printed $20 bill? One could only hope, nay, imagine.